Prompting or fine-tuning? Measuring well is still the smartest decision when adapting LLMs

At BBVA, we have been experimenting with large language models (LLMs) and, in general, with generative AI for some years now, a technology that has become the basis of new services such as Blue, BBVA’s virtual assistant.

A Large Language Model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence trained with a massive amount of text to understand and generate text in human language. Given the immense investment in data and computational capacity involved in training an LLM from scratch, at BBVA we use advanced models available on the market, such as OpenAI’s GPT family of models, which we adapt to our specific needs. In this article we discuss some use cases and applications of LLMs.

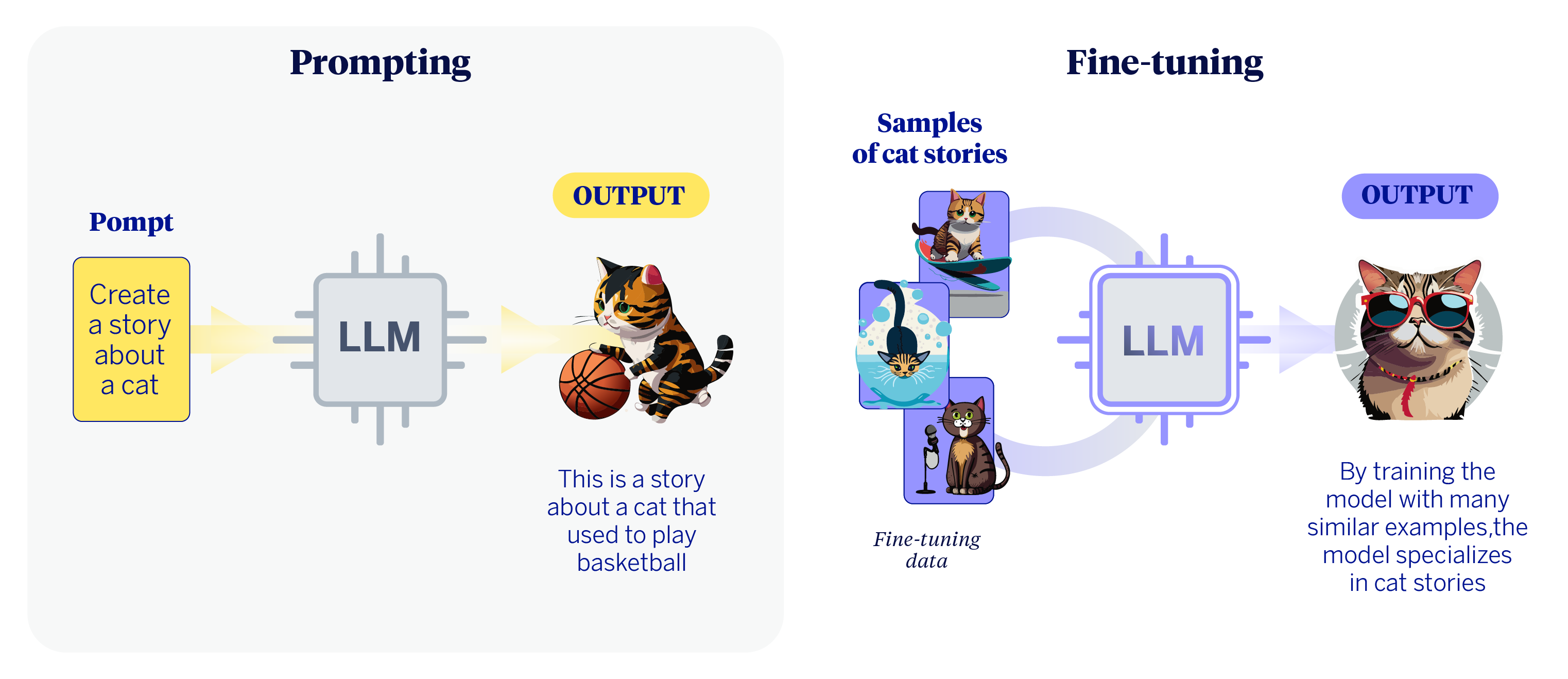

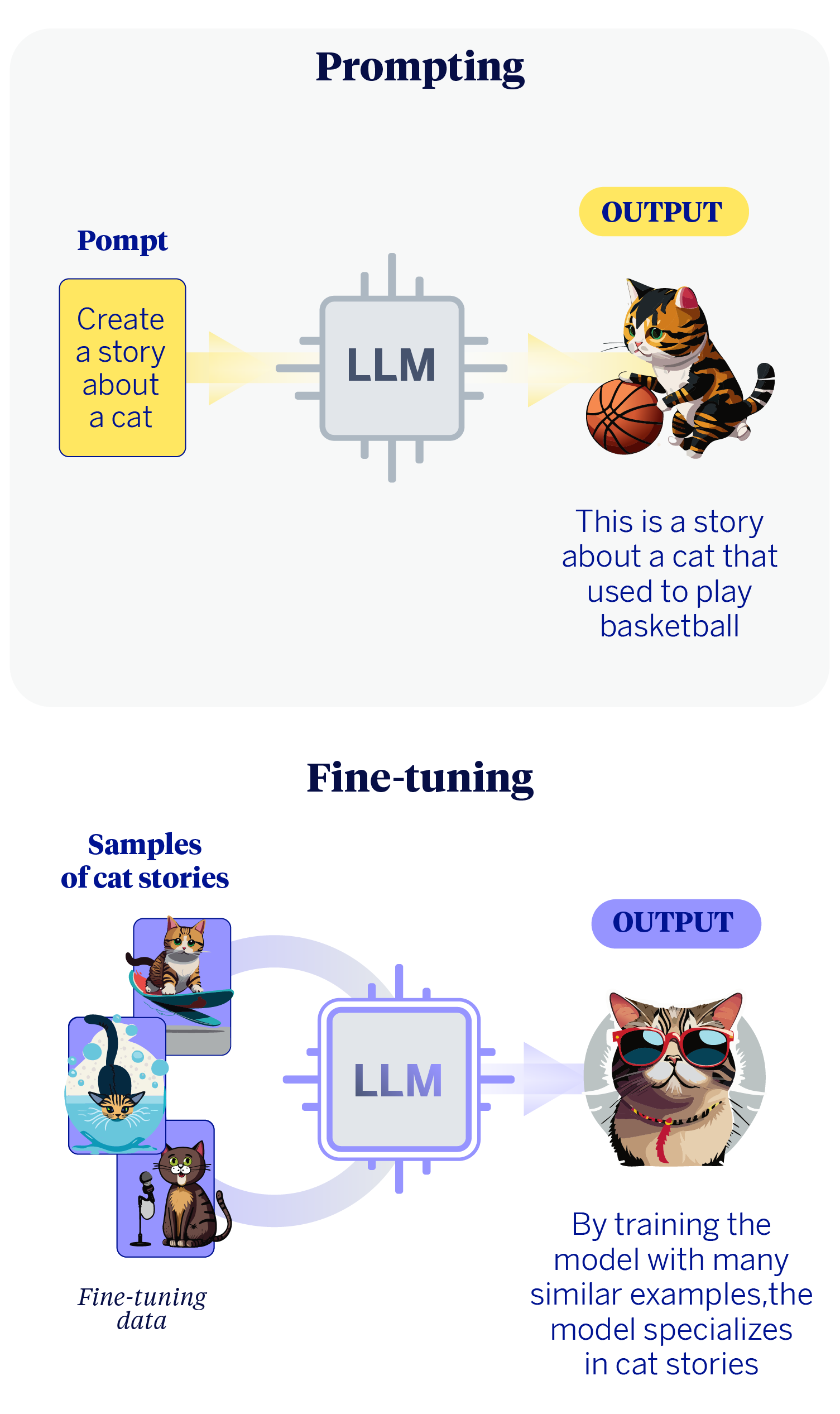

To adapt an LLM to a specific use case or business need, we can generally follow two paths. The first is prompt engineering, which consists of giving the model very clear and detailed instructions. It’s as if we were giving a very capable and versatile assistant a perfectly described list of tasks, with the context, restrictions, and desired response format so that it can execute them without errors. The assistant’s general ability is not modified, but the quality of the request is perfected to obtain an excellent result.

The second strategy we can follow is fine-tuning. This process goes a step further: instead of just giving instructions, we slightly modify the model’s base behavior by training it with hundreds or thousands of specific examples of our task. Following the analogy, it would be as if the assistant received intensive and specialized training, so that it becomes an expert in a specific area, such as interpreting financial reports, for example. Its fundamental knowledge does not change, but it acquires a new nuance, a specialization.

Now, before choosing one of the paths, it is crucial to establish validation cycles that allow us to measure the results from the beginning. The information we obtain from these evaluation processes will largely tell us the best path to follow next. In our experience working with LLMs at the BBVA AI Factory Gen AI Lab, we have learned that the most important question is not which path to take, but how we are going to measure if we have reached our destination. This article presents a methodology for adapting LLMs to specific use cases, focusing on the periodic measurement of results.

The key role of results evaluation for the use of LLMs

Language models are complex and, at times, their responses can be unpredictable. Therefore, evaluation is the pillar of any serious project. A good evaluation system allows us to objectively measure performance, guide improvements, and ensure that the final solution is reliable and secure. Our approach is based on an evaluation system with several components that work together:

- Automatic metrics and human review: On the one hand, we use automatic metrics that give us a quick idea of performance, such as accuracy or the percentage of correct answers. They are fast and scalable, but often only scratch the surface. On the other hand, human review allows us to analyze aspects and nuances that automatic evaluation is not correctly capturing, while also controlling its own operation.

- Continuous monitoring in production: A model’s performance can change when it faces real-world situations and users. Therefore, continuous monitoring is essential once the tool is in operation. This allows us to quickly detect if the model starts to fail with new questions we had not anticipated or if users interact in an unexpected way, so that we can react in time.

- Iterative validation from the beginning: Evaluation is not the last step, but a process that occurs simultaneously with development. Submitting models to validation cycles has allowed us to identify the root of many problems early on, which saves an enormous amount of time and resources. It has taught us that many deficiencies that seemed to require costly fine-tuning were resolved with more precise instructions, always guided by evaluation data.

This evaluation capability has been more decisive than any specific technique. Many experiments that seemed to require a fine-tuning process were resolved simply with more precise instructions or prompts and by measuring the results well.

A methodology for adapting LLMs

To organize our work, we have consolidated an iterative process that bases technical decisions on the data we obtain from the evaluation. It is a continuous improvement cycle.

Step 1: Define the objective and success metrics

Every project begins with a clear definition of the problem to be solved and the indicators that will tell us if we have been successful. It is crucial that these technical metrics are aligned with business objectives. For example, we translate goals such as “improving customer satisfaction” into measurable metrics, such as the percentage of inquiries resolved on first contact or user satisfaction scores.

Step 2: Agile iteration with prompting

We begin development using prompting due to its agility and low cost. This allows us to have a first functional version quickly and start measuring. We use different techniques depending on the problem:

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT): For problems that require reasoning, we ask the model to think step-by-step, breaking down its logic before giving the final answer.

- Few-Shot Prompting: We give the model concrete examples of what we want it to do, which helps it understand the pattern and expected format.

- Tool-Use and Agents: We allow the model to interact with external systems (such as databases or calculators) so that it can consult updated information or perform actions, overcoming the limitations of its static knowledge.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): We connect the model to an external and reliable source of information (a corpus of frequently asked questions, for example). Thus, its responses are based on specific and controlled data, which greatly reduces the risk of it inventing information.

Step 3: Continuous evaluation

Each new version of a prompt is subjected to our evaluation system. In this way, this step becomes a constant dialogue with the model: we propose a prompt, analyze the results to understand the failures and areas for improvement, and respond with a new prompt. This cycle is what allows us to refine the solution progressively.

Step 4: Controlled transition to fine-tuning processes

We only consider fine-tuning when prompting reaches a point where it stops improving and the metrics show us that we have not yet reached the objectives. This decision is always based on data and justifies the greater investment of time and resources required for fine-tuning. It is not a failure of prompting, but a strategic step to achieve a higher level of performance that, in some cases, only specialization can provide. When we do, we prioritize efficient techniques such as PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) or LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), which adjust only a small part of the model, reducing cost and risks.

Use cases at BBVA: lessons learned

Our methodology has been tested in multiple internal projects, leaving us with very clear lessons:

| ✅ Success story with well-evaluated prompting: | Developing internal LLM-based assistants for administrative and customer service tasks, a rigorous prompting and evaluation approach allowed us to resolve more than 90% of use cases without the need for fine-tuning. The key was to iterate on the prompts and evaluate rigorously: case coverage, response consistency, and satisfaction of the end users of the tool (BBVA employees). |

| ⚠️ Minimal improvement case with fine-tuning: | In a project with very ambiguous responses, we tried to improve performance with fine-tuning. The cost of obtaining well-labeled data was high, and the final improvement was very small compared to the solution we already had using prompting. Furthermore, the resulting system was less interpretable and more difficult to maintain. This showed us that, without a clear need and quality data, fine-tuning can be a large investment with few benefits. The resources invested could have been allocated to other projects with greater impact. |

| ❌ Cases with failure in input data: | In several RAG projects, we initially attributed the performance to the model. However, a detailed analysis of the failures indicated that the real problem was the quality of the information source consulted: outdated, poorly organized, or irrelevant data. By improving the information source and the instructions, performance improved significantly without touching the model. Again, good evaluation allowed us to avoid a more costly solution. |

Conclusion: the key to understanding is measuring

After working on the adaptation and implementation of LLMs, we conclude that the debate on whether to use prompting or fine-tuning is secondary. Practical experience shows us that the fundamental question is another: what problem are we solving and how are we going to measure if we are doing it well?

Prompt engineering is a fast and efficient way to obtain results and learn from the model. Fine-tuning is a powerful tool to specialize a model, but its use must be justified by a business need and supported by data. Ultimately, the success of an AI project is not measured by the complexity of the technique used, but by the rigor with which its performance and real impact are evaluated.

As we like to say on the team: “It’s not just about how you talk to the model, but how you evaluate what it tells you back.” That constant evaluation is what guarantees that we build robust, reliable, and truly useful AI solutions.